![A schematic brain depicted from above (Source: [url=http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cerebral_lobes.png]Wikimedia commons[/url])](http://www.cogsci.nl/images/stories/blog/hemispheres.png) As you probably know, brains of humans and other vertebrates consist of two halves, called hemispheres. By and large, both hemispheres carry out the same functions, but they are not identical. The best known asymmetry between the two hemispheres is the lateralization of language: The left hemisphere is dominant when it comes to language. Another obvious example is handedness: The right hand is primarily controlled by the left hemisphere, and vice versa, so handedness reflects a hemispheric specialization in the control of hand movements. Again, the left hemisphere is usually dominant.

As you probably know, brains of humans and other vertebrates consist of two halves, called hemispheres. By and large, both hemispheres carry out the same functions, but they are not identical. The best known asymmetry between the two hemispheres is the lateralization of language: The left hemisphere is dominant when it comes to language. Another obvious example is handedness: The right hand is primarily controlled by the left hemisphere, and vice versa, so handedness reflects a hemispheric specialization in the control of hand movements. Again, the left hemisphere is usually dominant.

The list goes on and on. Everywhere you look there are differences between left and right, which can often be traced back to asymmetries between the left and right hemispheres. Some differences, such as handedness, are obvious, some are subtle. And some are rather cute.

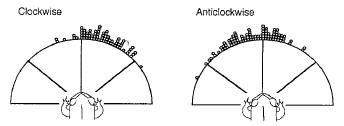

A while back I read a paper by Giorgio Vallortigara, one of the experts on lateralization, in which he made "a stroll through animals' left and right perceptual worlds." One figure in particular stuck in my mind:

So what are we looking at here? Vallortigara and colleagues investigated the predatory behavior of toads using the "worm test". They suspended worms, which toads enjoy very much, from a thread, and slowly brought the worms into the toads' field of view. Sometimes the worms entered the toads' visual field from the left, and sometimes from the right.

What the graph shows is that the direction from which the worm enters the toad's visual field makes a huge difference! If the worm enters from the right (anticlockwise), the toad often strikes immediately (sometimes it waits for a bit, but not always). But if the worm enters from the left (clockwise), the toad waits until the worm enters the right visual field. In other words, the toad has a striking preference (pun intended) for the right visual field when it comes to predatory behavior.

The results are very clear, but the explanation is a bit more complicated than at first sight it may seem. In most animals, the left visual field is processed by the right hemisphere, and vice versa. In animals with lateral eyes, placed on the side of the head, this is simply because the left visual field is seen mostly with the left eye, which projects to the right hemisphere, and vice versa. In animals with frontal eyes, such as humans, this is because of a phenomenon called "semi-decussation" (half-crossing). In those animals, there is a large overlap between the visual fields of both eyes, but for both eyes the left visual field goes to the right hemisphere, and vice versa (I won't go into too much detail here, but Wikipedia will tell you all about it). So with frontal eyes the reason is slightly more complicated, but the effect is the same: The left visual field goes to the right hemisphere, and vice versa.

So why are the results puzzling? Well, toads have frontal eyes, with a large binocular overlap. But they also have full decussation, rather than semi-decussation. So it would seem that, regardless of whether the worm is in the toad's left or right visual field, it is processed by both hemispheres. Which, in turn, would seem to make an explanation in terms of hemispheric specialization unlikely.

Nevertheless hemispheric specialization probably is the explanation for the results by Vallortigara and colleagues, if only because any other explanation is extremely unlikely. Perhaps toads have a type of semi-decussation that is anatomically different from, but functionally similar to that found in mammals? To be honest, I don't know, and the authors' thoughts on this are not very clear from the paper.

Intriguing stuff though...

References

Vallortigara, G. (2000). Comparative neuropsychology of the dual brain: a stroll through animals’ left and right perceptual worlds. Brain and Language, 73(2), 189-219.

Vallortigara, G., Rogers, L. J., Bisazza, A., Lippolis, G., & Robins, A. (1998). Complementary right and left hemifield use for predatory and agonistic behaviour in toads. NeuroReport, 9(14), 3341-3344.