Almost fifty years ago, Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky conducted their seminal studies on economic decision making, for which Kahneman later won the Nobel prize in economics. Their main message was simple: When it comes to matters of money, people make irrational choices based on gut feelings and intuitions; and these choices are not always in their own best interests.

We now live in the aftermath of the European debt crisis. The core of the eurocrisis was that several European member states were no longer able to finance their government debt; that is, countries like Greece (for whom the crisis is still far from over) had borrowed so much money, mostly from other European member states, that they could no longer pay the interest on these debts.

The way that the European Union (EU) has responded to the eurocrisis is a great example of the irrational economic decisions that Kahneman and Tversky demonstrated fifty years earlier. But on a massive scale—whereas Kahneman and Tversky studied the behavior of individuals, the eurocrisis showed how even economic decisions that affect an entire continent are based on gut feelings and flawed intuitions.

I'm not an economist. And I won't pretend to understand all the factors that played a role in the eurocrisis. But I do think it's useful to look at the eurocrisis with a few basic principles from psychology and economics in mind1. My goal here is to, by doing so, provide a coherent (though obviously very incomplete) answer to the questions: Why did poor member states, notably Greece, suffer so much during the crisis? What drove the EU to respond to the eurocrisis in the way they did? And what might be done better in the future?

Flying high and crashing hard

The eurocrisis hit somewhere around 2008. The result was that the entire eurozone saw their Gross Domestic Product (GDP) decline for a little while. The figure below shows data from two rich (Sweden and The Netherlands) and two poor (Cyprus and Greece) member states. The onset of the eurocrisis is visible as a dip around 2009.

Annual GDP growth rates for Sweden, The Netherlands, Cyprus, and Greece between 2000 and 2015. Data from the World Bank.

First things first: What is GDP? It's a measure of how much a country produces. For example, the GDP of Sweden consists in part (maybe even a large part) of Ikea furniture. And the GDP of Greece consists in part of olive oil. But developed economies produce a lot of services too: things like health care, customer support, etc. Services aren't as easy to quantify as physical products. Therefore, when it comes to GDP, for people who provide services, their production is their salary. If that doesn't make sense to you, that's ok: GDP is a messy concept, but it's useful as a rough indicator of how much a country produces.

When the GDP grows, the economy grows. When the GDP shrinks, as briefly happened for most countries around 2008, the economy shrinks. When the GDP continues to shrink for some time, as for Greece after 2008, most economists speak of a 'recession'.

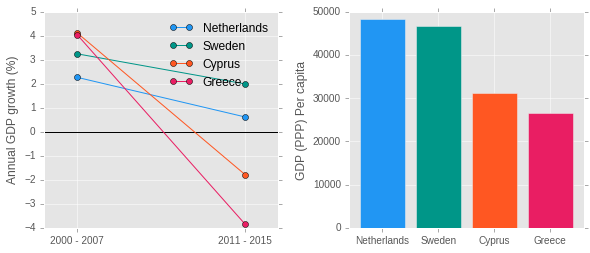

The figure above is a bit difficult to read, because GDP growth is noisy: there is a lot of year-to-year fluctuation that obscures long-term trends. Therefore, I've made another figure, shown below. On the left side, for each country, I've plotted the average annual GDP growth before (2000 - 2007) and after (the worst of) the crisis (2011 - 2015). On the right side, you see how wealthy the people in each country are.

Left: Pre- and post-crisis GDP growth rates for Sweden, The Netherlands, Cyprus, and Greece. Right: Post-crisis per capita GDP corrected for purchasing power. Data from the World Bank.

This figure highlights the following points:

- Greece and Cyprus are much poorer than Sweden and The Netherlands.

- Before the crisis, Greece and Cyprus were growing faster than Sweden and The Netherlands

- After the (worst of the) crisis, Greece and Cyprus were growing much slower than Sweden and The Netherlands. In fact, that's a euphemism: The crisis drove Greece and Cyprus into a major recession.

- The crisis didn't affect Sweden and The Netherlands very much. (If you live in one of these countries and disagree, then I kindly suggest that you visit Athens.)

So what's going on here? How can a country like Greece go from extreme economic growth (up to 6% annually!) to a major recession (down to -10% annually!), whereas other countries are more-or-less fine?

This may sound weird, but extreme economic growth is a sign of poverty. Economies can only grow very fast if they lag behind other countries, so that they can benefit from technologies that these other countries already have. To give a concrete (but made up) example, imagine that Greek farmers were still collecting olives by hand in 2000, whereas French farmers were already using an olive-gathering machine (which shakes trees and catches olives as they fall). If the Greek farmers also start using these olive-gathering machines, this could increase their production enormously. Whereas if the French farmers want to increase their production, they have to invent new, more efficient olive-collection techniques. And inventing new things is just more difficult than adopting existing things. So it's easy to grow if you're behind, and difficult to grow if you're ahead.

Extreme economic growth also makes it attractive to borrow money. Let's see why.

Imagine that you're a Greek businessman, and you borrow €100 against 5% interest while the Greek economy is growing by 6%. One year later, your €100 has grown to €106 (because of economic growth). Minus the €5 interest, you're still left with €101: a €1 profit. So you can make money by borrowing money, at least while the economy is growing rapidly. It's also attractive for rich, slower-growing countries, like Sweden, to lend money to Greece: Sweden has a lot of money to lend, and investing money in another country that is poorer and grows faster than your own is a money maker (among other things because poor countries are considered unsafe to invest in, and therefore have to pay more interest than rich countries. High interest compensates for the high risk.)

But now imagine that the world economy gets a hit, for example because of a clusterfuck with subprime mortgages in the US (i.e. mortgages to people who cannot afford them). And say that this slows down the Greek economy from, say, 6 to 3% annual growth. 3% growth is still not bad at all, but it's not enough to compensate for all the interest that needs to be paid on all the money that was borrowed! Now suddenly, every year, your borrowed €100 grows to €103 (because of economic growth), but minus the €5 interest, ends up shrinking to €98: a €2 loss. And the next year again (€96), and the next year again (€94), etc. Soon, you will have to borrow more money, just to be able to pay the interest on the money that you borrowed before! And once you start borrowing to pay interest, you're in a vicious cycle. And to make matters worse: Once other countries see that you're in a vicious cycle, they will no longer consider you a safe investment, and you will have to pay very high interest rates! At its worst, Greece paid around 25% interest, whereas Germany paid around 3%.

So: Poor countries can grow very fast (by adopting techniques from rich countries), then tend to borrow a lot of money during the good times (when they can easily pay the interest), and are then catastrophically affected by relatively minor economic setbacks (when they can suddenly no longer pay the interest).

Fuck you, pay me

Imagine that you've lend €1000 to help out a friend with money problems. Would you be happy if she then bought an expensive laptop before paying you back? Probably not. You'd feel that paying you back should be her top priority. And until that happens, she better show some modesty in her lifestyle.

This is how many people intuitively think about economy as well. And this intuition appears to have strongly guided EU economic policy.

The EU has forced economic austerity on Greece; that is, in order to receive 'help' (read: extra loans) Greece has had to massively cut back on government spending. For example, in a series of disastrous austerity packages, the Greek government has cut pensions, increased taxes, and frozen salaries of government officials. The logic behind these imposed austerity measures is simple: If the Greek government spends less money, then they can more easily pay back their creditors, mostly rich member states like Germany.

Intuitively, this may make sense: If you borrow money, then things are tight for a while, until you've paid it back. That's only fair; it matches our sense of, as Thomas Piketty likes to say, ce qui est juste et ce qui ne l'est pas. But Greece is a country, not a person; and debts don't work the same way for countries as they do for people.

The first problem is that all these enormous cutbacks have caused the Greek economy to shrink even further. Why? To give a concrete example (but with made-up numbers), imagine that the Greek government has a million functionaries that used to make about €30,000 per year; so that cost €30 billion per year. But this money is not lost; rather, it flows back into the Greek economy, because the functionaries spend most of the money that they make. And in terms of GDP, as I explained before, functionaries produce an amount that is equal to their combined salaries: €30 billion.

Now say that the Greek government, as part of an EU-imposed austerity package, reduces these salaries to €20,000 per year. This means that functionaries now produce only €20 billion—an economic shrinkage of €10 billion! The increase in unemployment that results from economic cutbacks is also bad for the economy: People who sit at home don't produce anything.

In other words, forcing cutbacks on Greece may give a rewarding sense of justice, and it may be a good way to get some money back in the very short term—that's probably true. But it has also suffocated the Greek economy even further, only making it more difficult to get money back in the longer term. And that's bad for everyone.

So why are these cutbacks nonetheless forced on the Greek government? In part, I suspect, this is simply because people are led by a gut feeling that tells them: You owe me money? Then fuck you, pay me.

Why the eurocrisis is unique

Economies that collapse under the weight of their debts—or rather the interest they need to pay on those debts—is of all times. But the Greek crisis is unique in a one crucial way: Greece is an independent country, and is responsible for its own finances. But Greece doesn't control its own currency. The Euro is controlled by the EU, and Greece is only a very small part of that.

If a country does control its own currency (so unlike Greece), then there is always a last resort to get rid of debts: printing money. If a country simply prints a lot of money, then it can use that to pay off debts. This is a very effective way to get rid of debts.

Printing money is really a last resort though, because there are adverse consequences too. Notably, it increases the amount of money without a corresponding increase in production, which means that you can buy less with the same amount of money: inflation. People don't like high inflation, because it makes their savings disappear. And neither do creditors, who see their loans paid back in a worthless currency. But printing money may still be the best option for a country in serious economic distress.

The Greek catch-22

But Greece cannot pay back their debts by printing Euros. The European Central Bank would never allow that. So what other options does Greece have? There are two unattractive options: defaulting on their debts, and leaving the eurozone.

If a country defaults on its debts, this means that it simply refuses to pay back—all debts are considered void. Countries have done this in the past. For example, Argentina has an interesting economic history in which they fell from being one of the richest countries in the world to being a struggling middle-income country, currently about half as rich as European countries. This fall from grace was accompanied by repeated debt defaulting by the Argentinian government. Not a shining example.

Nevertheless, defaulting is an efficient way to get rid of debts: You just say that they don't exist. But it's an even better way to make enemies. This is why countries rarely default, and prefer (if they can) to devalue their currency by printing money. Printing money is, in a sense, a soft approach to defaulting—creditors get screwed either way.

You've probably heard of the three big credit-rating agencies: Moody's, Standard & Poors (S&P), and Fitch. Their credit ratings indicate how likely countries are to default on their debts. Before the eurocrisis, the Greek S&P credit rating was a decent A+ ("upper medium grade"), meaning that Greece was considered a fairly safe place to put your money; at its worst, the Greek rating had dropped to CC ("extremely speculative"), meaning that it's very doubtful that you will every see your money again.

Another way for Greece to get rid of their debts is to leave the eurozone, and to go back to their previous currency: the Drachma. Unlike the UK, Greece has a good reason to do this: Once they control their own currency again, they can print money to pay off their debts, as I described above.

Leaving the eurozone may be accompanied by chaos and mayhem. Or it may not. No-one knows, and for now it seems that the Greeks do not want to find out. But they may change their minds.

Avoiding the catch-22: the Macron way

Emmanuel Macron may become the next French president. If you read this after May 7 2017, then I hope that this prediction has become fact. Because Macron has some very sensible ideas about the eurozone. His ideas are mostly common sense, and my impression is that they are mainstream among economists. But they are a tough sell to the proverbial man on the street, who lets himself be guided by his gut feelings. So far, Macron is the only (potentially) influential politician who is brave enough to express these sensible ideas publicly.

Macron points out (as I also explained above) that cutbacks cause economies to shrink, whereas investments cause economies to grow; therefore, struggling member states, such as Greece, should be encouraged to invest in their economy, and not to implement cutbacks that only drive their economy further into a recession. Just to be clear: That's the opposite of what the EU has actually been doing to Greece.

So where do struggling member states get the money to invest in their economies? According to Macron, rich member states should financially support poor member states. Not by having rich member states lend money to poor member states, as the EU has been doing so far. Because such loans only increases the poor member states' debts, and the interest that they have to pay every year—whereas not being able to pay interest is the problem to begin with. Macron means that rich member states, such as Germany and (let's be generous) France, give billions of Euros to poor member states, such as Greece and Portugal. As a gift—no strings attached.

This goes against most people's intuition of ce qui est juste et ce qui ne l'est pas. Surely, if someone owes you money to begin with, then you don't just give them even more money? To those dirty, corrupt, money-grabbing, lazy Greeks? Hell no!

But when it comes to countries, it does make sense. Not only does financial support help poor member states (obviously), but it also helps rich member states, who need a place to export their products to. If Greeks are too poor to buy Renault cars and Siemens washing machines, then the French and the Germans suffer. EU member states depend on each other; and if one goes down, they all suffer.

Financially supporting your poor neighbors sounds like socialism, but it's not. Even the US economy—known for its cold-blooded capitalism—is based on this principle. Money from rich states, such as New York (about as rich as Switzerland), flows into poor states, such as Missisipi (about as rich as Greece). Not so much money that all states are equally rich. But enough for poor states to survive. And Macron wants to implement the same system in the eurozone.

To conclude: I hope that this post has helped you to better understand some aspects of the eurocrisis and the Greek catch-22. Many things in economics are a matter of opinion: Whether you feel that it should be every man for himself, or that the strong should support the weak—that's up to you. And whether or not you feel that economic growth is even a goal to strive for—that's up to you. But not everything is a matter of opinion. For example, that the Greek crisis hurts all European member states, and that it can only be truly resolved through debt relief (i.e. giving Greece money) strikes me as a fact. And that the EU doesn't want to relieve Greece of its debt is not a rational choice; rather, it seems to be based on a flawed fuck-you-pay-me intuition—which Kahneman and Tversky might have already predicted fifty years ago.

-

Because economics is not my expertise, I did my best not to include a single original thought in this post, and to stick to what I believe is mainstream economic thinking. Among other resources, I've relied on the following very accessible books: The ascent of money by Niall Ferguson, Le capital au XXIe siècle by Thomas Piketty, and The weak suffer what they must? by Yanis Varoufakis. ↩