This afternoon I was eating a sub in the Plymouth harbor, finally enjoying a bit of sun, which we haven't seen much of this summer. I was joined by a seagull chick. It was presumably hoping to score a piece of my sub.

So why share this wholly unremarkable footage with you? The bird sat there for something like 10 minutes (gulls are nothing if not patient and persistent) and after a while it struck me that it didn't appear to look at me (or my sub) much at all. It seemed to be continuously distracted by something to its right or left, even though there was nothing there, at least nothing as interesting as my sub (I imagine). Then it dawned on me that, in contrast to appearance, the gull must have been looking at me all the time, but with different parts of its eye!

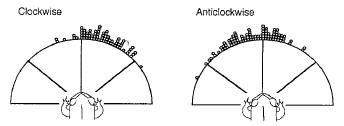

![Visual acuity drops of rapidly with distance from the fovea (source: [url=http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fovea_centralis]Wikipedia[/url])](http://www.cogsci.nl/images/stories/blog/figures/foveal_acuity.png) As you probably know, we see only a small part of our surroundings with high resolution and in color. This is the part that falls onto our fovea, a small, extra dense part of the retina. Foveal vision corresponds to about the size of a thumb at arm's length.

As you probably know, we see only a small part of our surroundings with high resolution and in color. This is the part that falls onto our fovea, a small, extra dense part of the retina. Foveal vision corresponds to about the size of a thumb at arm's length.

Yet we feel as though we have a complete and full-color perception of our entire visual field. In large part, this is because our eyes are mobile: If we think about something, we immediately look at it (bring it into foveal vision) to get a crisp view of the object in question.

So what …

![A schematic brain depicted from above (Source: [url=http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cerebral_lobes.png]Wikimedia commons[/url])](http://www.cogsci.nl/images/stories/blog/hemispheres.png) As you probably know, brains of humans and other vertebrates consist of two halves, called hemispheres. By and large, both hemispheres carry out the same functions, but they are not identical. The best known asymmetry between the two hemispheres is the lateralization of language: The left hemisphere is dominant when it comes to language. Another obvious example is handedness: The right hand is primarily controlled by the left hemisphere, and vice versa, so handedness reflects a hemispheric specialization in the control of hand movements. Again, the left hemisphere is usually dominant.

As you probably know, brains of humans and other vertebrates consist of two halves, called hemispheres. By and large, both hemispheres carry out the same functions, but they are not identical. The best known asymmetry between the two hemispheres is the lateralization of language: The left hemisphere is dominant when it comes to language. Another obvious example is handedness: The right hand is primarily controlled by the left hemisphere, and vice versa, so handedness reflects a hemispheric specialization in the control of hand movements. Again, the left hemisphere is usually dominant.

![A globe (source: [url=http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Globe.jpg]Wikimedia Commons[/url])](http://www.cogsci.nl/images/stories/blog/globe.jpg) Lewis and colleagues were quick to distance themselves from Morton's distinctly racist views, and emphasized that differences in cranial capacity do not reflect differences in intelligence, as Morton had believed. But this, of course, begs the question: If not intelligence, what do differences in cranial capacity reflect?

Lewis and colleagues were quick to distance themselves from Morton's distinctly racist views, and emphasized that differences in cranial capacity do not reflect differences in intelligence, as Morton had believed. But this, of course, begs the question: If not intelligence, what do differences in cranial capacity reflect?